Alphonso Lingis – Passion

(Click HERE to open this article in the reader.)

Cerro Aconcagua in the Argentine Andes, rising to 22, 837 feet, is the highest mountain in the Americas, and the highest mountain outside the Himalayas. It harbors several glaciers, the largest one some 10 kilometers long. I trekked its lower reaches and that evening went to a lodge at its base. At the front desk there was a self-published book entitled Aconcagua, which, after a look at it, I bought, and read that evening.

The author, Juan Aguilar, is a psychotherapist, based in Buenos Aires. He tells of one of his patients, Miguel, a 51-year-old man, university educated, married with two children, running a successful real estate business. Miguel did not really suffer from chronic depression, but he complained that meaning had somehow gone out of his life. There were no sexual or emotional problems in his relationship with his wife, but conversation with her went down the familiar paths and sexual intercourse had become routine caresses and strokings with the familiar relief. He had become completely knowledgeable about the real estate business and skilled in dealing with buyers and sellers, but now sales no longer surprised or exhilarated him. He made a lot of money, but spending it no longer brought satisfaction. Improvements to his house, new appliances, a new car: nothing seemed to add anything to his life. “I buy things, spend money, and then don’t see the sense of it,” he said to the therapist. “Buying and selling real estate—does that have some meaning for me, for my life? Having a home, a wife, children—is that what having a life means? Anyhow you don’t really ‘have’ a wife, children; they have their own lives. And I don’t see what that means, you know.” After a long pause, he said, “I feel that I am like an actor on a little stage, making gestures and pronouncing my lines before other actors. Everything I say and do responds to what my employees say, what my customers say. After work everything I say and do responds to what my wife says, what my children say, what the neighbors say. Like I am in a web where the strings pull and I pull back. The worth, the meaning of what I say and do is just in that little stage. Is that all there is?”

He had bought some philosophy books. He had taken some philosophy courses in the university, so he felt that he could read and understand them. “But I need guidance,” he told the therapist. “And I need someone to help me connect the ideas of philosophy with my own situation.”

After a few sessions in which the Juan listened to his patient tell his life and his trouble, he proposed that Miguel climb Aconcagua. He said that he would accompany him.

The ascent of Aconcagua by the south face involves routes that are among the most difficult that mountain climbers attempt. But ascent on the north face can be done without ropes and crampons. However, the almost seven kilometers altitude, the extreme cold—the wind chill can drop to -80° F—storm winds, and avalanches make this ascent also dangerous, and Aconcagua has one of the highest mountain death tolls in the world. Juan had twice climbed it, although each time turning back before reaching the summit. Privately he hoped that encouraging his patient would give him the extra drive and he would this time attain the summit.

Juan and Miguel set the date in February, midsummer, when Miguel could arrange six weeks leave from work. They had four months to prepare, keep to a healthy diet, no alcohol or cigarettes, weight training five days a week, an hour of cardio exercises daily.

The book recounts the climb. Arrival at the base, days of acclimatization. Then beginning the ascent. Patches of loose rock, then ice. Frazzled ice, crevasses. The heavy fatigue as the climb rises. Unrelenting howling winds. Juan keeping up a high-spirited demeanor, to support Miguel. But beginning to doubt his own physical stamina. Times when he imagines Miguel injured or collapsing in altitude sickness, his own efforts to revive him and descend to safety failing. Thinking of the Hippocratic oath; first do not harm. Then the day Miguel is gasping for air, his hands immobilized with the cold, stopping, abandoning the climb the rest of the day. Juan anguished wondering what he could possibly be risking Miguel’s life for, risking his own. Looking up to the summit, visible now, but not seeming any closer as they make less distance each day. Then the sky darkens, heavy snowfall, whiteout. They are two days from the summit. The winds hurl against them, they have to crouch and grip on the ice beneath them. The mountainside and the air are clotted with white; the contours of the ice about them vanish in the density of white. They turn back, a slow descent as the white everywhere darkens to ash grey and night falls. Four days to descend to the base camp. The book ends without the therapist relating what happened then, in the months and years that followed, without giving an appraisal of Miguel’s subsequent state or recounting what changes he may have made in his life.

I found myself strangely gripped by this book in the following days, and have thought back to it several times since. This book unsettled me; I did not know what to make of it.

Miguel’s despondency and his questions were about meaning, but this therapy was no talking cure, did not proceed by interpretation. It did not show him a meaningful realm to live his life; they went to stay weeks on the brute rocks and ice of the uninhabitable mountain. A domain of grandeur, but also forms of rock and formlessness of snow and sky refusing human apprehension, where the human figure and its intentions were reduced to insignificance, the mountain driving them off. They would be agape with wonder, that state that opens upon what is beyond the practicable and comprehensible, visions beyond what the human mind can imagine. They would be swollen with anxiety and terror before dangers beyond what means they could have to parry them, and sullen physical fatigue and the lassitude that no longer seeks to resist death. Impassioned states, that totally fill and throb in mind and body, disconnected from, disconnecting the experience and knowledge and enterprises of the past. Not opening upon a future: what was the utility of knowing these extremities of wonder, anxiety, terror, desolation, toxic lassitude? Are these not states that crush people, those who come to psychotherapy because grief, rancor, bitterness, jealousy, rage consume them and make them unable to conduct their lives?

What are passions? Let us separate the term “passion ” from the terms “emotion,” “affects,” “feeling,” “sentiment,” and “mood.” These terms, which gained currency in 18th century and have acquired the stamp of objectivity, are now the terms used in psychology, ethics, aesthetics, and legal and political discourse, as well as in evolutionary biology, anthropology, and neurobiology. They belong to a specific kind of analysis and explanation. Feelings or emotions are taken to be psychic reactions to body disturbances caused by things or events that strike one from the outside. They are conceived as transitory events occurring to the self, which subsists behind or beneath them. Feelings and emotions produce bodily reactions, gestures, and expressions, which can be observed by others. But the self distinct from them is taken to be something invisible, unperceivable from the outside, known by only one witness, from within, a sphere of privacy. I have a sense of myself when I take a distance from my feelings, observe them, judge them. The self can manage its feelings and emotions, control them, integrate them with its intentions and projects.

Let us note that the sense of the self is not constant. Much of the time the tasks and the implements are laid out before us each day: the toothbrush, razor, and shower in the morning, the bus to work, the tasks laid out in the factory or office. A layout of directives in the things. We do what there is to be done. And the postures and manipulations we have picked up from others, and pass on to others. In all that we do not have a distinct sense of a self as an individual source of thoughts and decisions.

What I will here call “passion” we find in Homer’s Iliad, Sophocles, Shakespeare’s tragedies, Dostoyevsky, Melville and in a great deal of our literature and cinema. Vehement wonder, lust, rage, courage, or terror, jealousy, grief fill one’s mind and body, swollen with surging energy and heightened sensitivity. All our senses are enflamed. Impassioned states give us the experience of being self-identical and undivided. Mind and body are one. Rage saturates the mind and is felt throughout the body, in the postural axis, in the clenched fists and beating heart, the trembling limbs.

Impassioned states are not experienced as events occurring to the self, which would be experienced beneath or above them. Instead, the self arises in the passion, takes form in it. In wonder or in rage the sense of self surges, the self surges, and it is an awestruck or enraged self. In impassioned states the self arises, a force that confronts, makes claims on others and on the world.

Passionate outbreaks carve out space and time in distinctive ways. Impassioned wonder, anger, terror, jealousy, and mourning mark out a territory where my life and my honor are cut off from what is not mine, where what is deserved is bounded from what is undeserved, where my intimates are separated from strangers. Passionate outbreaks disconnect from the public world and stake out a territory that is my space, my world.

And passionate outbreaks structure time in a distinctive way. They do not take place in a never-ending line of time segmented into minutes, hours, and days, nor in the time we experience as stretching back and containing our past actions and encounters and extending forward where foreseen plans and projects are inscribed. Instead the time of an impassioned experience disconnects from the continuum of life and nature. Passion intensely and completely fills a present. In rage or mourning this throbbing present is backed up to what has just happened. What has just happened separates from the continuously passing field. In terror what is just about to happen, what is imminent, rises in high relief before the swollen pressure of the present. In the unending line of the time of nature and society, there disconnects this new structure consisting of the bloated present, the immediate past, and the imminent future.

In current language “having an experience” designates something unexpected, intense, and with a limited endurance in which it evolves and comes to an end, such that it gives rise to a narrative. Having an experience is having an impassioned experience, an experience undergone in passion. Observing an event, however unusual, is not having an experience.

Awestruck wonder, that state in which our engagement in a practicable field is interrupted and we find ourselves abruptly opened upon regions and events that leave us stunned, that empty out our chattering mind and disconnect the skills and manipulations of our bodies—wonder is the fundamental impassioned state. Finding oneself, as Immanuel Kant says, beholding massive mountains treading skyward, gorges with raging streams cutting deeper in them, wastelands lying in deep shadow and inviting melancholy meditation. (CJ 129) Standing by night on the frozen tundra of the far north, and seeing, high overhead the Northern Lights shimmer in constantly changing colors like great sheer curtains in the black of outer space.

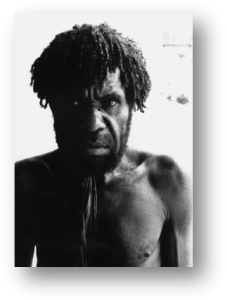

One is isolated, in the midst of the raging electrical storm, before the vast inhuman icescape of Antarctica, which fill the whole of space about one. One is exposed, and feels the pounding of life within one’s undivided mind and body. The self is this deep, primate throbbing of life, insistent and indubitable.

There is an element of wonder, before the astonishing, the bewildering, the overwhelming, in every passion—in rage, in terror, in grief, in sexual passion.

Impassioned lustful love is possessed with the apparition of the unforeseeable, uncomprehendable in another. Erotic passion is high-spirited, making claims on the world and on busied and detached others, confident and assertive.

Wrath asserts “Me!” and “my people!” before events of the world, in front of others. It proclaims one’s worth and dignity. It gives rise to our primary sense of justice and injustice.

Wrath asserts “Me!” and “my people!” before events of the world, in front of others. It proclaims one’s worth and dignity. It gives rise to our primary sense of justice and injustice.

Wrath is involved in deep friendship and love. We rarely break out in rage before slights to our person or our actions done by people with whom we have no friendship. Our vexation passes; their disparagement is as indifferent to us as they are. But when our most cherished friends and lovers slight us, our anger asserts how much we care for their regard and how injured we are by their disdain.

Impassioned courage fills mind and body as one, arises in hard compacted energies before threatening forces and unsurveyable menaces, and takes a stand before the intolerable.

Fatigue and pain are biological signals that alert us to harm in our organism and motivate us to act to remedy the assault it is suffering. But the awakening of passion also resolves us to endure fatigue and pain. Impassioned obstinacy and courage pit their force against lassitude and pain. The self rises in this obstinacy and courage, severe and bent on triumphing in them.

Passionate mourning is not simply an impotent sense of loss. It involves the claim that the loss, of one’s beloved, one’s child is unjust, unacceptable; it maintains this claim against the fates. It takes courage to mourn passionately.

In impassioned fear, terror, we find ourselves before imminent death in battle, in earthquakes, in flaming buildings, or when we are first told that the doctors have identified a disease in its terminal phase. We find ourselves overwhelmed, shattered, paralyzed, but also energized to scream and curse in refusal and to flee. There is some element of terror in impassioned envy, jealousy, and melancholy.

In impassioned fear, terror, we find ourselves before imminent death in battle, in earthquakes, in flaming buildings, or when we are first told that the doctors have identified a disease in its terminal phase. We find ourselves overwhelmed, shattered, paralyzed, but also energized to scream and curse in refusal and to flee. There is some element of terror in impassioned envy, jealousy, and melancholy.

A passionate state, which fills mind and body, disconnects from the patterns of the past and blocks foresight of consequences, shuts off the warnings and counsel of prudence and rationality. A passionate state also excludes other passionate states. Rage snuffs out fear; an enraged person is fearless, as military commanders know. But fear can shut off anger; the abrupt appearance of a mighty enemy force provokes flight. Greed shuts out empathy and grief before the misfortune of others, grief over the death of a rich relative.

It is striking that impassioned states transform in a certain direction. Terror characteristically passes into shame. Impassioned jealousy turns into rage. Rage often turns into mourning. Impassioned ambition often turns into guilt, although guilt does not typically turn into ambition. Unrequited love turns into hatred. “In Shakespeare’s Winter’s Tale . . . King Leontes . . . passes from jealousy to rage, from rage to remorse, from remorse to mourning, and, finally, from mourning to wonder.” (VP 36)

Homer’s Iliad, Sophocles, Shakespeare’s tragedies, Milton, Dostoyevsky show us a world where events are launched, counteracted, redirected, consummated and consumed in impassioned states. Recent literature such as Knut Hamsun’s The Growth of the Soil and Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude show the eruption of passions forcing the zigzag lines that plot the lives of individuals and of a community.

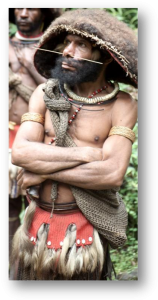

We today understand and share the passions recounted in Homer; passionate states are transhistorical and transcultural. And we share them with other species, rabbits terrorized by dogs, enraged pheasants defending their chicks against predators, elephants and dolphins that mourn their dead. Humans have always been confident that they recognize and identify impassioned states in other species.

The psychology of feelings and emotions constructed by 18th century philosophers and psychologists fits in with the norms of everyday life in the political economy set up to maximize order and productivity. Albert Hirschman found that 17th and 18th century political philosophers declared that a political system must promote avarice above all, because avarice blocks out “the interruptive, short-term episodes of anger, grief, falling in love . . . that push aside the everyday attention to the present and the future on which our shared world of everyday work and economic life depends” (VP 33). “By its orientation to the long- and middle-term future, avarice also blocks structurally the entire set of passions that give priority to the past: anger, shame, regret, and mourning” (VP 34). The writings of these political philosophers forcefully added to the discrediting of the passions. A psychology that would enjoin us to take a distance from passions, view them objectively, from the outside, as others view them, that pathologizes the passions, is in fact assigning priority to everyday life in the political economy set up to maximize order and productivity, making it normative. But then we have to recognize that this life can be emptied by the erosion of meaning.

Impassioned states are not reactions proportionate to the situation; they are excessive. Our organisms are material systems in which, through excretion, secretion, evaporation lacks develop, which are experienced as needs. These open the organism to the outside; its senses scan the environment and the organism moves to take hold of substances and sustenance to satisfy its needs. The pleasure in needs satisfied closes in on the content in contentment and rest. But our organisms are material systems that generate energies, energies in excess of what they require to satisfy their needs.

Impassioned states are not reactions proportionate to the situation; they are excessive. Our organisms are material systems in which, through excretion, secretion, evaporation lacks develop, which are experienced as needs. These open the organism to the outside; its senses scan the environment and the organism moves to take hold of substances and sustenance to satisfy its needs. The pleasure in needs satisfied closes in on the content in contentment and rest. But our organisms are material systems that generate energies, energies in excess of what they require to satisfy their needs.

Impassioned outbreaks surge with excess energies generated within. There is the pride of standing forth, the thrill of rushing onward, the melodic movements that pick up the throbbing rhythm of events and landscapes. The surging of excess energies within, felt in exuberance, seeks out the muscle strains and fatigue of hard labor and hard play, which intensify one’s sense of surging energies, one’s sense of oneself.

Wrath and terror respond to powerful and unexpected threats to our domain or our life. But awestruck wonder seeks out the grandiose and the terrible, releasing its excess energies without return, gratuitously. High-spiritedness greets the collapse of methodic manipulations, the absurdity of events in human society and in nature, seeks them out to affirm them in peals of laughter. The philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche separated the surging of excess energies that are used for self-aggrandizement from the joyous exhilaration that releases excess energies without asking anything in return. These last he called the noble moments in life.

For philosopher Georges Bataille passions arise in the transgression of boundaries and taboos. Nature and society set limits to where we can go and what we can do. Beyond lies the unknown, the unpredictable, danger. Our excess energies drive us to plunge across the boundaries and taboos in exhilaration and anxiety. Anxiety in sensing danger and death. Exhilaration in sensing the surge of superabundant energies within. Passions are made of exhilaration and anxiety. They plunge into the unknown, the unknowable, the unmanipulatable, the unpracticable.

In erotic passion we know extreme pleasure and extreme anxiety. Lust is addressed to the other, in whose visible and palpable materiality there stir unknown visions, dreams, longings. Our caressing eyes and hands pass repetitively, aimlessly over the body of another, not gathering information, not knowing what they are seeking. They stir spasms of torment and pleasure in the other’s body. We violate the space of another, break through the identity that others constitute for the other and that the other assumes for him- or herself. We disrobe the other and ourselves, setting aside the protection and uniforms that clothe the body in the posts and functions of productive work and society. Our practical posture collapses, we abandon our limbs and organs to another, abandon dignity and self-respect, and identity. We drift in moaning and sighs, exhalations, the opacity of pleasure and night. La petite mort, the French say.

In erotic passion we know extreme pleasure and extreme anxiety. Lust is addressed to the other, in whose visible and palpable materiality there stir unknown visions, dreams, longings. Our caressing eyes and hands pass repetitively, aimlessly over the body of another, not gathering information, not knowing what they are seeking. They stir spasms of torment and pleasure in the other’s body. We violate the space of another, break through the identity that others constitute for the other and that the other assumes for him- or herself. We disrobe the other and ourselves, setting aside the protection and uniforms that clothe the body in the posts and functions of productive work and society. Our practical posture collapses, we abandon our limbs and organs to another, abandon dignity and self-respect, and identity. We drift in moaning and sighs, exhalations, the opacity of pleasure and night. La petite mort, the French say.

One never regrets having made a fool of oneself for sex or for love. One regrets not having dared.

Impassioned states are not simply transitory outbursts; they give rise to passionate attachment to things. Passionate attachments are quite different from the utilitarian attachment to things, or the attachment to things for their symbolic value. As passionate attachments philosophers Giles Deleuze and Félix Guattari cite food, for compulsive eaters, bulimics and anorexics; a dress, lingerie, or shoes, for fetishists; a domestic dog or cat (TP 129). But so many things can function as the point of passionate attachment—a butterfly collection, a cabin in the wilderness, an endangered species of bird, the silverback gorillas of Ruanda. One is not merely attached to symbols, but to the dense and enigmatic reality of something alien to the human organism. Composing sounds into a music the world has never before heard, putting paints on canvas can appear to a man or a woman worth devoting all one’s energies and resources, all one’s life to.

What is distinctive in passionate attachment is that the self undergoes metamorphosis. In the attachment to things for their utilitarian function, or for their symbolic value, the self asserts its independence and sovereignty. But in one’s attachment to a cat or a horse one feels the vital movements of cats or horses within oneself, and one senses one’s own sentiments and impulses in cats or horses. A fetishist sees lingerie animated with his voluptuous languor and feels lingerie embedded in his own body. A hunter acquires the sharp eyes, wariness, stealth movement, speed, readiness to spring and race, and the exhilaration of the beast he hunts, which are available for stalking prey but also for gamboling down the hills into the river, dancing, and sexual contests. A mountaineer acquires the hardness, rigor, obstinacy, endurance, and taciturnity of the mountain.

In erotic passion one feels oneself existing in the other’s attachment to oneself, in the sense the other has of oneself; one becomes his or her lover. And the other feels him- or herself existing in the intensity of the lover’s attachment to him or her, becomes the beloved. Passionate love does not produce communion or fusion, but instead an intense sense of oneself lodged in the other and an intense sense of the other lodged in oneself.

In erotic passion one feels oneself existing in the other’s attachment to oneself, in the sense the other has of oneself; one becomes his or her lover. And the other feels him- or herself existing in the intensity of the lover’s attachment to him or her, becomes the beloved. Passionate love does not produce communion or fusion, but instead an intense sense of oneself lodged in the other and an intense sense of the other lodged in oneself.

The passion discovers ever more enigmas in the object of its attachment, in increasing wonder and beguilement, moves in fear before its or her vulnerability, anger before what threatens him or her. Ever more vehement passions crowd into it.

Friedrich Nietzsche contrasts passionate knowledge of a woman, a silverback gorilla, a landscape with the observation that takes a distance from it as an object, the observation we call “objective.” Passionate attachment moves through different passions, each revealing a new perspective and depth. We do not think we know a woman through a series of anatomical, psychological, cultural, sociological, observations. We think we do not know a woman until we have melted before her kindness and feared her wrath, been anguished before her vulnerability and retreated before her power, been illuminated by her insights and charmed by her foolishness, until she has made us laugh as we have never laughed, made us weep in misery.

For impassioned states exclude one another but also attract one another.

The self devoted to order and productivity, the prudent and calculating self, seeks to manage its feelings and emotions, control them, integrate them in the service of its practical initiatives. Nietzsche, to the contrary, envisages a life that would harbor conflicting passions that would intensify and enflame one another.

Anyone who manages to experience the history of humanity as a whole as his own history will feel in an enormously generalized way all the grief of an invalid who thinks of health, of an old man who thinks of the dreams of his youth, of a lover deprived of his beloved, of the martyr whose ideal is perishing, of the hero on the evening after a battle that has decided nothing but brought him wounds and the loss of his friend. But if one endured, if one could endure this immense sum of grief of all kinds while yet being the hero who, as the second day of battle breaks, welcomes the dawn and his fortune, being a person whose horizon encompasses thousands of years past and future, being the heir of all the nobility of all past spirits—an heir with a sense of obligation, the most aristocratic of old nobles and at the same time the first of a new nobility—the like of which no age has yet seen or dreamed of; if one could burden one’s soul with all of this—the oldest, the newest, losses, hopes, conquests, and the victories of humanity; if one could finally contain all this in one soul and crowd it into a single feeling—this would surely have to result in a happiness that humanity has not known so far; the happiness of a god full of power and love, full of tears and laughter, a happiness that, like the sun in the evening, continually bestows its inexhaustible riches, pouring them into the sea, feeling richest, as the sun does, when even the poorest fisherman is rowing with golden oars! This godlike feeling would then be called—being human. (GS §337)

Nietzsche here envisions not a harmonious integration of our different emotions, but a taking upon oneself the deepest grief and sorrow over the most terrible losses, the boldest hopes, the most intense sense of honor of humans throughout their history, crowding these conflicting passions within oneself. They oppose one another and enflame one another. That would result in the most intense high-spiritedness, exhilaration, exultation, “a happiness that humanity has not known so far.”

This state Nietzsche then identifies with god, nature, and humanity. It would be “the happiness of a god full of power and love, full of tears and laughter.” For Nietzsche does not conceive the highest kind of life, the divine life, as immobilized in bliss, but a life pounding with power and love, tears and laughter. There is no laughter without tears, for laughter is the release of power and pleasure before the unworkable, the collapse of utility and meaning, the absurd—and these call forth tears also. Love of someone is love because it is in conflict with power over him or her. But in the same person these two conflicting drives intensify one another.

What Nietzsche identifies as the happiness that humanity has not known so far, the exultation made of the greatest intensity of conflicting passions, is the most truthful state. It opens widest upon, it engages most intensely with all that is and happens. Discovering that all things, sheltering and nourishing and also indifferent and hostile are “entangled, ensnared, enamored” it says Yes to all that is and happens, loving one’s life, loving life, loving the world (Z IV, The Drunken Song, 9. 10). We must trust our joy, for joy is the most truthful state.

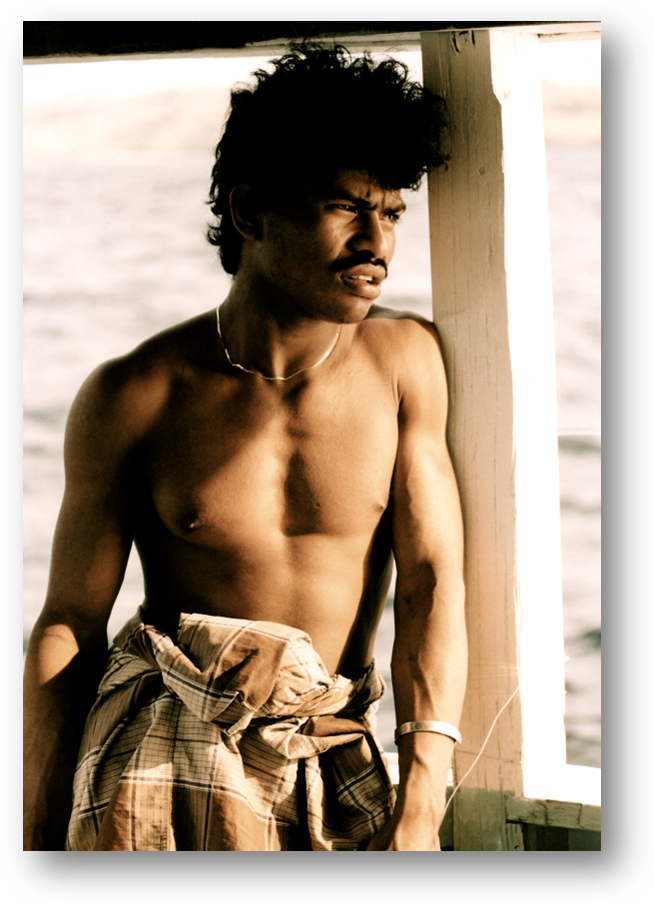

Nietzsche then says that the intensification and crowding together of contradictory passions would produce “a happiness that, like the sun in the evening, continually bestows its inexhaustible riches, pouring them into the sea, feeling richest, as the sun does, when the poorest fisherman is rowing with golden oars!” Here this state is identified with nature, with the sun, hub of nature, which gives inexhaustibly its energies to all life without asking for anything in return, and in this gratuitous outpouring creates all life and creates beauty. Pouring its gold into the sea such that the poorest fisherman rows with golden oars. That state would be the highest and also most natural state of humanity.

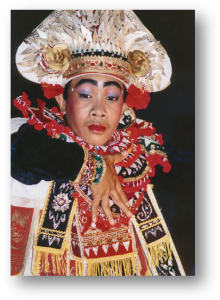

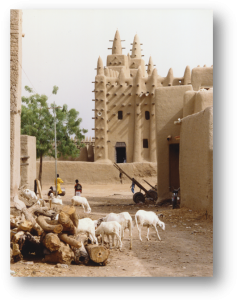

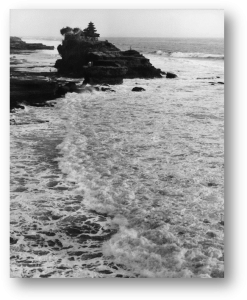

The exultant embrace of the world with superabundant energies is creative. Creative of knowledge, which reveals and opens us, far beyond the limited sphere of human needs and concerns, to the vastness and complexity of the universe, to the songs of the cicadas that emerge only every 17 years, the songs of the sperm whales in the ocean abysses, the solar wind that illuminates the curtains of the aurora borealis, the 67 moons circling the planet Jupiter. Creative of paintings and sculptures that enhance and hold the ephemeral blush of a young woman, the glitter of autumn on a mountain lake. Creative of temples that enshrine mountains and caves and sky. Creative of songs and dance with which we join the songs and dance of nature. “‘O Zarathustra’ the animals said, ‘to those who think as we do, all things themselves are dancing. They join hands and laugh and flee—and come back’” (Z III, The Convalescent, 2).

The exultant embrace of the world with superabundant energies is creative. Creative of knowledge, which reveals and opens us, far beyond the limited sphere of human needs and concerns, to the vastness and complexity of the universe, to the songs of the cicadas that emerge only every 17 years, the songs of the sperm whales in the ocean abysses, the solar wind that illuminates the curtains of the aurora borealis, the 67 moons circling the planet Jupiter. Creative of paintings and sculptures that enhance and hold the ephemeral blush of a young woman, the glitter of autumn on a mountain lake. Creative of temples that enshrine mountains and caves and sky. Creative of songs and dance with which we join the songs and dance of nature. “‘O Zarathustra’ the animals said, ‘to those who think as we do, all things themselves are dancing. They join hands and laugh and flee—and come back’” (Z III, The Convalescent, 2).

The domain of the passions, surging in anxiety and exhilaration, is, Georges Bataille says, laughter, tears, poetry, tragedy and comedy, play, dance, music, ecstasy, the magic of childhood, the funereal horror, eroticism (individual or not, spiritual or sensual, corrupt, cerebral or violent, or delicate), the divine and the diabolical, the sacred, of which sacrifice is the most intense aspect, intoxication, combat, crime, cruelty, disgust. This domain outside of utilitarian existence Bataille calls “the festive” (AS III, 230-1)

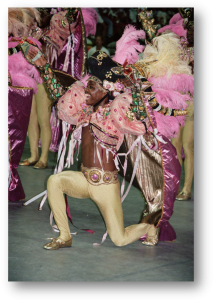

In designating the multiplicity of impassioned experiences “the festive,” Bataille indicates that the impassioned self is not isolated, closed in itself. We laugh and we weep with others. Before the collapse of laborious projects or pompous behavior or the disintegration of a sententious discourse into nonsense we laugh, we look at one another and are indubitably aware of what each sees and the pleasure each knows in peals of laughter; we are transparent to one another. In tragic and comic art our extreme emotions surge together; in dance and carnival our anxiety and exhilaration surge like crests of waves spreading among us, in erotic passion each is excited by the excitement of the other, the pleasure and torment of each invades the other.

Juan and Miguel descended Cerro Aconcagua and returned to Buenos Aires. Then what? They had not simply known feelings and emotions on the mountain that they could observe, judge, manage; they had known impassioned states that were undivided between mind and body. Far from family and business that had constructed Miguel’s identity, far from office that had constructed Juan’s therapist identity, there surged forth an impassioned self, an awestruck self, a self asserting itself in terror and rage, a hitherto unknown unsuspected self that in obstinacy and courage pitted itself against exhaustion and pain. They had known the anxiety and the exhilaration of transgressing the boundaries set by nature and society.

These are not experiences that reveal the meaning of life and of the world; they encounter the inhuman, the destructive, the indifference in the substance of reality. They are not experiences that will be integrated in Miguel’s everyday life in Buenos Aires, a life devoted to order and productivity and to the accumulation of commodities beyond all needs and wants. They open, outside of the sphere of reason and work, upon the domain of the festive.

Will Miguel driven violently from Cerro Aconcagua find himself bent on returning? Will he find himself attached to remote and forbidding landscapes, going back to the Andes, going to the Sahara, to the Ice continent of Antarctica?

Will he deepen his passionate attachment in reading books, viewing documentaries, himself speaking, writing, creating? Will he become an environmental activist?

Or perhaps he will remember the climb as a time in which he dared and risked as never before, and in the pain and exhaustion found he had resources to endure he did not know he had. Perhaps he finds in his office other mountains to climb. Perhaps he will rethink his real estate business, learn new computer technology to make it more efficient, train new employees. Perhaps his days, his weekends will be filled with things that have to be done, things that have to be said. Perhaps the urgency of things that have to be done and said will take the place of the meaning he had once sought for.

Three times now Juan has gone to Aconcagua and turned back before reaching the summit. Which of his next patients—banker, middle-aged housewife, college student–is going to hear the advice to climb Aconcagua with him?

References

Georges Bataille, The Accursed Share, vols II & III, trans. Robert Hurley

(NY: Zone Books, 1993. Cited as AS.

Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, trans. Brian

Massumi (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987). Cited as T.P

Philip Fisher, The Vehement Passions (Princeton: Princeton University

Press, 2002). Cited as VP.

Immanuel Kant, Critique of Judgment, trans. Werner S. Pluhar (Indianapolis: Hackett,

1987). Cited as CJ.

Friedrich Nietzsche, The Gay Science, trans. Walter Kaufmann (NY:

Vintage, 1974). Cited as GS.

Thus Spoke Zarathustra, in The Portable Nietzsche, trans. Walter

Kaufmann (NY: Viking, 1968). Cited as Z.