Alphonso Lingis – Passion

(Click HERE to open this article in the reader.)

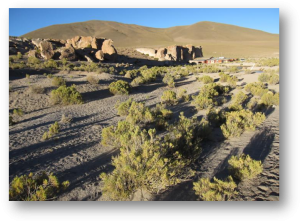

Cerro Aconcagua in the Argentine Andes, rising to 22, 837 feet, is the highest mountain in the Americas, and the highest mountain outside the Himalayas. It harbors several glaciers, the largest one some 10 kilometers long. I trekked its lower reaches and that evening went to a lodge at its base. At the front desk there was a self-published book entitled Aconcagua, which, after a look at it, I bought, and read that evening.

The author, Juan Aguilar, is a psychotherapist, based in Buenos Aires. He tells of one of his patients, Miguel, a 51-year-old man, university educated, married with two children, running a successful real estate business. Miguel did not really suffer from chronic depression, but he complained that meaning had somehow gone out of his life. There were no sexual or emotional problems in his relationship with his wife, but conversation with her went down the familiar paths and sexual intercourse had become routine caresses and strokings with the familiar relief. He had become completely knowledgeable about the real estate business and skilled in dealing with buyers and sellers, but now sales no longer surprised or exhilarated him. He made a lot of money, but spending it no longer brought satisfaction. Improvements to his house, new appliances, a new car: nothing seemed to add anything to his life. “I buy things, spend money, and then don’t see the sense of it,” he said to the therapist. “Buying and selling real estate—does that have some meaning for me, for my life? Having a home, a wife, children—is that what having a life means? Anyhow you don’t really ‘have’ a wife, children; they have their own lives. And I don’t see what that means, you know.” After a long pause, he said, “I feel that I am like an actor on a little stage, making gestures and pronouncing my lines before other actors. Everything I say and do responds to what my employees say, what my customers say. After work everything I say and do responds to what my wife says, what my children say, what the neighbors say. Like I am in a web where the strings pull and I pull back. The worth, the meaning of what I say and do is just in that little stage. Is that all there is?”

He had bought some philosophy books. He had taken some philosophy courses in the university, so he felt that he could read and understand them. “But I need guidance,” he told the therapist. “And I need someone to help me connect the ideas of philosophy with my own situation.”

After a few sessions in which the Juan listened to his patient tell his life and his trouble, he proposed that Miguel climb Aconcagua. He said that he would accompany him.

The ascent of Aconcagua by the south face involves routes that are among the most difficult that mountain climbers attempt. But ascent on the north face can be done without ropes and crampons. However, the almost seven kilometers altitude, the extreme cold—the wind chill can drop to -80° F—storm winds, and avalanches make this ascent also dangerous, and Aconcagua has one of the highest mountain death tolls in the world. Juan had twice climbed it, although each time turning back before reaching the summit. Privately he hoped that encouraging his patient would give him the extra drive and he would this time attain the summit.

Juan and Miguel set the date in February, midsummer, when Miguel could arrange six weeks leave from work. They had four months to prepare, keep to a healthy diet, no alcohol or cigarettes, weight training five days a week, an hour of cardio exercises daily.

The book recounts the climb. Arrival at the base, days of acclimatization. Then beginning the ascent. Patches of loose rock, then ice. Frazzled ice, crevasses. The heavy fatigue as the climb rises. Unrelenting howling winds. Juan keeping up a high-spirited demeanor, to support Miguel. But beginning to doubt his own physical stamina. Times when he imagines Miguel injured or collapsing in altitude sickness, his own efforts to revive him and descend to safety failing. Thinking of the Hippocratic oath; first do not harm. Then the day Miguel is gasping for air, his hands immobilized with the cold, stopping, abandoning the climb the rest of the day. Juan anguished wondering what he could possibly be risking Miguel’s life for, risking his own. Looking up to the summit, visible now, but not seeming any closer as they make less distance each day. Then the sky darkens, heavy snowfall, whiteout. They are two days from the summit. The winds hurl against them, they have to crouch and grip on the ice beneath them. The mountainside and the air are clotted with white; the contours of the ice about them vanish in the density of white. They turn back, a slow descent as the white everywhere darkens to ash grey and night falls. Four days to descend to the base camp. The book ends without the therapist relating what happened then, in the months and years that followed, without giving an appraisal of Miguel’s subsequent state or recounting what changes he may have made in his life.

I found myself strangely gripped by this book in the following days, and have thought back to it several times since. This book unsettled me; I did not know what to make of it.

Miguel’s despondency and his questions were about meaning, but this therapy was no talking cure, did not proceed by interpretation. It did not show him a meaningful realm to live his life; they went to stay weeks on the brute rocks and ice of the uninhabitable mountain. A domain of grandeur, but also forms of rock and formlessness of snow and sky refusing human apprehension, where the human figure and its intentions were reduced to insignificance, the mountain driving them off. They would be agape with wonder, that state that opens upon what is beyond the practicable and comprehensible, visions beyond what the human mind can imagine. They would be swollen with anxiety and terror before dangers beyond what means they could have to parry them, and sullen physical fatigue and the lassitude that no longer seeks to resist death. Impassioned states, that totally fill and throb in mind and body, disconnected from, disconnecting the experience and knowledge and enterprises of the past. Not opening upon a future: what was the utility of knowing these extremities of wonder, anxiety, terror, desolation, toxic lassitude? Are these not states that crush people, those who come to psychotherapy because grief, rancor, bitterness, jealousy, rage consume them and make them unable to conduct their lives?

What are passions? Let us separate the term “passion ” from the terms “emotion,” “affects,” “feeling,” “sentiment,” and “mood.” These terms, which gained currency in 18th century and have acquired the stamp of objectivity, are now the terms used in psychology, ethics, aesthetics, and legal and political discourse, as well as in evolutionary biology, anthropology, and neurobiology. They belong to a specific kind of analysis and explanation. Feelings or emotions are taken to be psychic reactions to body disturbances caused by things or events that strike one from the outside. They are conceived as transitory events occurring to the self, which subsists behind or beneath them. Feelings and emotions produce bodily reactions, gestures, and expressions, which can be observed by others. But the self distinct from them is taken to be something invisible, unperceivable from the outside, known by only one witness, from within, a sphere of privacy. I have a sense of myself when I take a distance from my feelings, observe them, judge them. The self can manage its feelings and emotions, control them, integrate them with its intentions and projects.

Let us note that the sense of the self is not constant. Much of the time the tasks and the implements are laid out before us each day: the toothbrush, razor, and shower in the morning, the bus to work, the tasks laid out in the factory or office. A layout of directives in the things. We do what there is to be done. And the postures and manipulations we have picked up from others, and pass on to others. In all that we do not have a distinct sense of a self as an individual source of thoughts and decisions.

What I will here call “passion” we find in Homer’s Iliad, Sophocles, Shakespeare’s tragedies, Dostoyevsky, Melville and in a great deal of our literature and cinema. Vehement wonder, lust, rage, courage, or terror, jealousy, grief fill one’s mind and body, swollen with surging energy and heightened sensitivity. All our senses are enflamed. Impassioned states give us the experience of being self-identical and undivided. Mind and body are one. Rage saturates the mind and is felt throughout the body, in the postural axis, in the clenched fists and beating heart, the trembling limbs.

Impassioned states are not experienced as events occurring to the self, which would be experienced beneath or above them. Instead, the self arises in the passion, takes form in it. In wonder or in rage the sense of self surges, the self surges, and it is an awestruck or enraged self. In impassioned states the self arises, a force that confronts, makes claims on others and on the world.

Passionate outbreaks carve out space and time in distinctive ways. Impassioned wonder, anger, terror, jealousy, and mourning mark out a territory where my life and my honor are cut off from what is not mine, where what is deserved is bounded from what is undeserved, where my intimates are separated from strangers. Passionate outbreaks disconnect from the public world and stake out a territory that is my space, my world.

And passionate outbreaks structure time in a distinctive way. They do not take place in a never-ending line of time segmented into minutes, hours, and days, nor in the time we experience as stretching back and containing our past actions and encounters and extending forward where foreseen plans and projects are inscribed. Instead the time of an impassioned experience disconnects from the continuum of life and nature. Passion intensely and completely fills a present. In rage or mourning this throbbing present is backed up to what has just happened. What has just happened separates from the continuously passing field. In terror what is just about to happen, what is imminent, rises in high relief before the swollen pressure of the present. In the unending line of the time of nature and society, there disconnects this new structure consisting of the bloated present, the immediate past, and the imminent future.

In current language “having an experience” designates something unexpected, intense, and with a limited endurance in which it evolves and comes to an end, such that it gives rise to a narrative. Having an experience is having an impassioned experience, an experience undergone in passion. Observing an event, however unusual, is not having an experience.

Awestruck wonder, that state in which our engagement in a practicable field is interrupted and we find ourselves abruptly opened upon regions and events that leave us stunned, that empty out our chattering mind and disconnect the skills and manipulations of our bodies—wonder is the fundamental impassioned state. Finding oneself, as Immanuel Kant says, beholding massive mountains treading skyward, gorges with raging streams cutting deeper in them, wastelands lying in deep shadow and inviting melancholy meditation. (CJ 129) Standing by night on the frozen tundra of the far north, and seeing, high overhead the Northern Lights shimmer in constantly changing colors like great sheer curtains in the black of outer space.

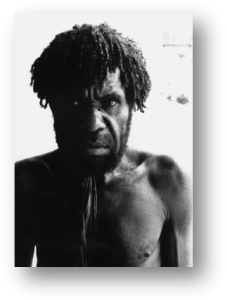

One is isolated, in the midst of the raging electrical storm, before the vast inhuman icescape of Antarctica, which fill the whole of space about one. One is exposed, and feels the pounding of life within one’s undivided mind and body. The self is this deep, primate throbbing of life, insistent and indubitable.

There is an element of wonder, before the astonishing, the bewildering, the overwhelming, in every passion—in rage, in terror, in grief, in sexual passion.

Impassioned lustful love is possessed with the apparition of the unforeseeable, uncomprehendable in another. Erotic passion is high-spirited, making claims on the world and on busied and detached others, confident and assertive.

Wrath asserts “Me!” and “my people!” before events of the world, in front of others. It proclaims one’s worth and dignity. It gives rise to our primary sense of justice and injustice.

Wrath asserts “Me!” and “my people!” before events of the world, in front of others. It proclaims one’s worth and dignity. It gives rise to our primary sense of justice and injustice.

Wrath is involved in deep friendship and love. We rarely break out in rage before slights to our person or our actions done by people with whom we have no friendship. Our vexation passes; their disparagement is as indifferent to us as they are. But when our most cherished friends and lovers slight us, our anger asserts how much we care for their regard and how injured we are by their disdain.

Impassioned courage fills mind and body as one, arises in hard compacted energies before threatening forces and unsurveyable menaces, and takes a stand before the intolerable.

Fatigue and pain are biological signals that alert us to harm in our organism and motivate us to act to remedy the assault it is suffering. But the awakening of passion also resolves us to endure fatigue and pain. Impassioned obstinacy and courage pit their force against lassitude and pain. The self rises in this obstinacy and courage, severe and bent on triumphing in them.

Passionate mourning is not simply an impotent sense of loss. It involves the claim that the loss, of one’s beloved, one’s child is unjust, unacceptable; it maintains this claim against the fates. It takes courage to mourn passionately.

In impassioned fear, terror, we find ourselves before imminent death in battle, in earthquakes, in flaming buildings, or when we are first told that the doctors have identified a disease in its terminal phase. We find ourselves overwhelmed, shattered, paralyzed, but also energized to scream and curse in refusal and to flee. There is some element of terror in impassioned envy, jealousy, and melancholy.

In impassioned fear, terror, we find ourselves before imminent death in battle, in earthquakes, in flaming buildings, or when we are first told that the doctors have identified a disease in its terminal phase. We find ourselves overwhelmed, shattered, paralyzed, but also energized to scream and curse in refusal and to flee. There is some element of terror in impassioned envy, jealousy, and melancholy.

A passionate state, which fills mind and body, disconnects from the patterns of the past and blocks foresight of consequences, shuts off the warnings and counsel of prudence and rationality. A passionate state also excludes other passionate states. Rage snuffs out fear; an enraged person is fearless, as military commanders know. But fear can shut off anger; the abrupt appearance of a mighty enemy force provokes flight. Greed shuts out empathy and grief before the misfortune of others, grief over the death of a rich relative.

It is striking that impassioned states transform in a certain direction. Terror characteristically passes into shame. Impassioned jealousy turns into rage. Rage often turns into mourning. Impassioned ambition often turns into guilt, although guilt does not typically turn into ambition. Unrequited love turns into hatred. “In Shakespeare’s Winter’s Tale . . . King Leontes . . . passes from jealousy to rage, from rage to remorse, from remorse to mourning, and, finally, from mourning to wonder.” (VP 36)

Homer’s Iliad, Sophocles, Shakespeare’s tragedies, Milton, Dostoyevsky show us a world where events are launched, counteracted, redirected, consummated and consumed in impassioned states. Recent literature such as Knut Hamsun’s The Growth of the Soil and Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude show the eruption of passions forcing the zigzag lines that plot the lives of individuals and of a community.

We today understand and share the passions recounted in Homer; passionate states are transhistorical and transcultural. And we share them with other species, rabbits terrorized by dogs, enraged pheasants defending their chicks against predators, elephants and dolphins that mourn their dead. Humans have always been confident that they recognize and identify impassioned states in other species.

The psychology of feelings and emotions constructed by 18th century philosophers and psychologists fits in with the norms of everyday life in the political economy set up to maximize order and productivity. Albert Hirschman found that 17th and 18th century political philosophers declared that a political system must promote avarice above all, because avarice blocks out “the interruptive, short-term episodes of anger, grief, falling in love . . . that push aside the everyday attention to the present and the future on which our shared world of everyday work and economic life depends” (VP 33). “By its orientation to the long- and middle-term future, avarice also blocks structurally the entire set of passions that give priority to the past: anger, shame, regret, and mourning” (VP 34). The writings of these political philosophers forcefully added to the discrediting of the passions. A psychology that would enjoin us to take a distance from passions, view them objectively, from the outside, as others view them, that pathologizes the passions, is in fact assigning priority to everyday life in the political economy set up to maximize order and productivity, making it normative. But then we have to recognize that this life can be emptied by the erosion of meaning.

Impassioned states are not reactions proportionate to the situation; they are excessive. Our organisms are material systems in which, through excretion, secretion, evaporation lacks develop, which are experienced as needs. These open the organism to the outside; its senses scan the environment and the organism moves to take hold of substances and sustenance to satisfy its needs. The pleasure in needs satisfied closes in on the content in contentment and rest. But our organisms are material systems that generate energies, energies in excess of what they require to satisfy their needs.

Impassioned states are not reactions proportionate to the situation; they are excessive. Our organisms are material systems in which, through excretion, secretion, evaporation lacks develop, which are experienced as needs. These open the organism to the outside; its senses scan the environment and the organism moves to take hold of substances and sustenance to satisfy its needs. The pleasure in needs satisfied closes in on the content in contentment and rest. But our organisms are material systems that generate energies, energies in excess of what they require to satisfy their needs.

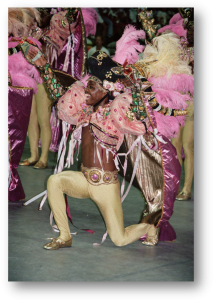

Impassioned outbreaks surge with excess energies generated within. There is the pride of standing forth, the thrill of rushing onward, the melodic movements that pick up the throbbing rhythm of events and landscapes. The surging of excess energies within, felt in exuberance, seeks out the muscle strains and fatigue of hard labor and hard play, which intensify one’s sense of surging energies, one’s sense of oneself.

Wrath and terror respond to powerful and unexpected threats to our domain or our life. But awestruck wonder seeks out the grandiose and the terrible, releasing its excess energies without return, gratuitously. High-spiritedness greets the collapse of methodic manipulations, the absurdity of events in human society and in nature, seeks them out to affirm them in peals of laughter. The philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche separated the surging of excess energies that are used for self-aggrandizement from the joyous exhilaration that releases excess energies without asking anything in return. These last he called the noble moments in life.

For philosopher Georges Bataille passions arise in the transgression of boundaries and taboos. Nature and society set limits to where we can go and what we can do. Beyond lies the unknown, the unpredictable, danger. Our excess energies drive us to plunge across the boundaries and taboos in exhilaration and anxiety. Anxiety in sensing danger and death. Exhilaration in sensing the surge of superabundant energies within. Passions are made of exhilaration and anxiety. They plunge into the unknown, the unknowable, the unmanipulatable, the unpracticable.

In erotic passion we know extreme pleasure and extreme anxiety. Lust is addressed to the other, in whose visible and palpable materiality there stir unknown visions, dreams, longings. Our caressing eyes and hands pass repetitively, aimlessly over the body of another, not gathering information, not knowing what they are seeking. They stir spasms of torment and pleasure in the other’s body. We violate the space of another, break through the identity that others constitute for the other and that the other assumes for him- or herself. We disrobe the other and ourselves, setting aside the protection and uniforms that clothe the body in the posts and functions of productive work and society. Our practical posture collapses, we abandon our limbs and organs to another, abandon dignity and self-respect, and identity. We drift in moaning and sighs, exhalations, the opacity of pleasure and night. La petite mort, the French say.

In erotic passion we know extreme pleasure and extreme anxiety. Lust is addressed to the other, in whose visible and palpable materiality there stir unknown visions, dreams, longings. Our caressing eyes and hands pass repetitively, aimlessly over the body of another, not gathering information, not knowing what they are seeking. They stir spasms of torment and pleasure in the other’s body. We violate the space of another, break through the identity that others constitute for the other and that the other assumes for him- or herself. We disrobe the other and ourselves, setting aside the protection and uniforms that clothe the body in the posts and functions of productive work and society. Our practical posture collapses, we abandon our limbs and organs to another, abandon dignity and self-respect, and identity. We drift in moaning and sighs, exhalations, the opacity of pleasure and night. La petite mort, the French say.

One never regrets having made a fool of oneself for sex or for love. One regrets not having dared.

Impassioned states are not simply transitory outbursts; they give rise to passionate attachment to things. Passionate attachments are quite different from the utilitarian attachment to things, or the attachment to things for their symbolic value. As passionate attachments philosophers Giles Deleuze and Félix Guattari cite food, for compulsive eaters, bulimics and anorexics; a dress, lingerie, or shoes, for fetishists; a domestic dog or cat (TP 129). But so many things can function as the point of passionate attachment—a butterfly collection, a cabin in the wilderness, an endangered species of bird, the silverback gorillas of Ruanda. One is not merely attached to symbols, but to the dense and enigmatic reality of something alien to the human organism. Composing sounds into a music the world has never before heard, putting paints on canvas can appear to a man or a woman worth devoting all one’s energies and resources, all one’s life to.

What is distinctive in passionate attachment is that the self undergoes metamorphosis. In the attachment to things for their utilitarian function, or for their symbolic value, the self asserts its independence and sovereignty. But in one’s attachment to a cat or a horse one feels the vital movements of cats or horses within oneself, and one senses one’s own sentiments and impulses in cats or horses. A fetishist sees lingerie animated with his voluptuous languor and feels lingerie embedded in his own body. A hunter acquires the sharp eyes, wariness, stealth movement, speed, readiness to spring and race, and the exhilaration of the beast he hunts, which are available for stalking prey but also for gamboling down the hills into the river, dancing, and sexual contests. A mountaineer acquires the hardness, rigor, obstinacy, endurance, and taciturnity of the mountain.

In erotic passion one feels oneself existing in the other’s attachment to oneself, in the sense the other has of oneself; one becomes his or her lover. And the other feels him- or herself existing in the intensity of the lover’s attachment to him or her, becomes the beloved. Passionate love does not produce communion or fusion, but instead an intense sense of oneself lodged in the other and an intense sense of the other lodged in oneself.

In erotic passion one feels oneself existing in the other’s attachment to oneself, in the sense the other has of oneself; one becomes his or her lover. And the other feels him- or herself existing in the intensity of the lover’s attachment to him or her, becomes the beloved. Passionate love does not produce communion or fusion, but instead an intense sense of oneself lodged in the other and an intense sense of the other lodged in oneself.

The passion discovers ever more enigmas in the object of its attachment, in increasing wonder and beguilement, moves in fear before its or her vulnerability, anger before what threatens him or her. Ever more vehement passions crowd into it.

Friedrich Nietzsche contrasts passionate knowledge of a woman, a silverback gorilla, a landscape with the observation that takes a distance from it as an object, the observation we call “objective.” Passionate attachment moves through different passions, each revealing a new perspective and depth. We do not think we know a woman through a series of anatomical, psychological, cultural, sociological, observations. We think we do not know a woman until we have melted before her kindness and feared her wrath, been anguished before her vulnerability and retreated before her power, been illuminated by her insights and charmed by her foolishness, until she has made us laugh as we have never laughed, made us weep in misery.

For impassioned states exclude one another but also attract one another.

The self devoted to order and productivity, the prudent and calculating self, seeks to manage its feelings and emotions, control them, integrate them in the service of its practical initiatives. Nietzsche, to the contrary, envisages a life that would harbor conflicting passions that would intensify and enflame one another.

Anyone who manages to experience the history of humanity as a whole as his own history will feel in an enormously generalized way all the grief of an invalid who thinks of health, of an old man who thinks of the dreams of his youth, of a lover deprived of his beloved, of the martyr whose ideal is perishing, of the hero on the evening after a battle that has decided nothing but brought him wounds and the loss of his friend. But if one endured, if one could endure this immense sum of grief of all kinds while yet being the hero who, as the second day of battle breaks, welcomes the dawn and his fortune, being a person whose horizon encompasses thousands of years past and future, being the heir of all the nobility of all past spirits—an heir with a sense of obligation, the most aristocratic of old nobles and at the same time the first of a new nobility—the like of which no age has yet seen or dreamed of; if one could burden one’s soul with all of this—the oldest, the newest, losses, hopes, conquests, and the victories of humanity; if one could finally contain all this in one soul and crowd it into a single feeling—this would surely have to result in a happiness that humanity has not known so far; the happiness of a god full of power and love, full of tears and laughter, a happiness that, like the sun in the evening, continually bestows its inexhaustible riches, pouring them into the sea, feeling richest, as the sun does, when even the poorest fisherman is rowing with golden oars! This godlike feeling would then be called—being human. (GS §337)

Nietzsche here envisions not a harmonious integration of our different emotions, but a taking upon oneself the deepest grief and sorrow over the most terrible losses, the boldest hopes, the most intense sense of honor of humans throughout their history, crowding these conflicting passions within oneself. They oppose one another and enflame one another. That would result in the most intense high-spiritedness, exhilaration, exultation, “a happiness that humanity has not known so far.”

This state Nietzsche then identifies with god, nature, and humanity. It would be “the happiness of a god full of power and love, full of tears and laughter.” For Nietzsche does not conceive the highest kind of life, the divine life, as immobilized in bliss, but a life pounding with power and love, tears and laughter. There is no laughter without tears, for laughter is the release of power and pleasure before the unworkable, the collapse of utility and meaning, the absurd—and these call forth tears also. Love of someone is love because it is in conflict with power over him or her. But in the same person these two conflicting drives intensify one another.

What Nietzsche identifies as the happiness that humanity has not known so far, the exultation made of the greatest intensity of conflicting passions, is the most truthful state. It opens widest upon, it engages most intensely with all that is and happens. Discovering that all things, sheltering and nourishing and also indifferent and hostile are “entangled, ensnared, enamored” it says Yes to all that is and happens, loving one’s life, loving life, loving the world (Z IV, The Drunken Song, 9. 10). We must trust our joy, for joy is the most truthful state.

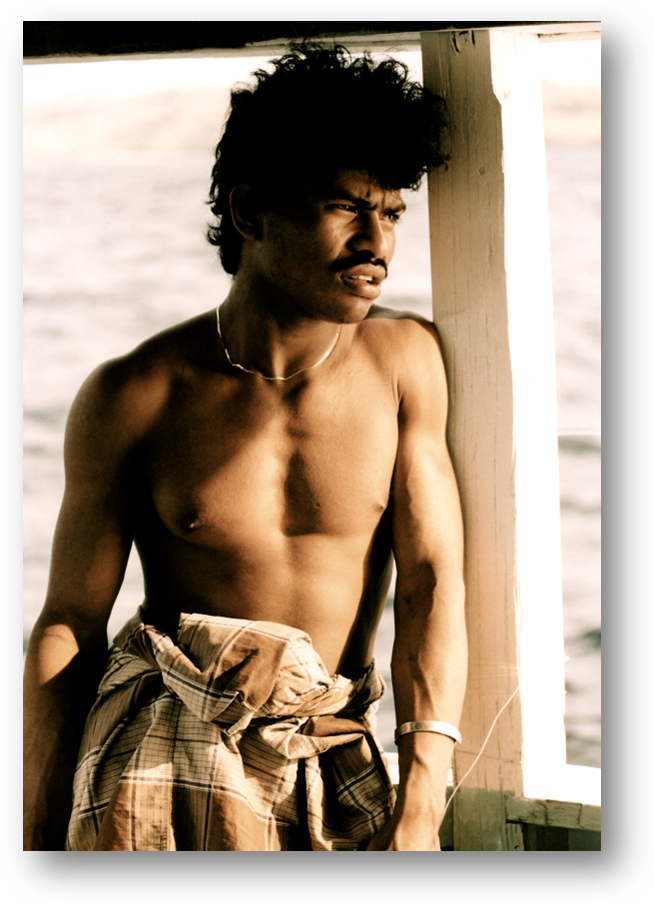

Nietzsche then says that the intensification and crowding together of contradictory passions would produce “a happiness that, like the sun in the evening, continually bestows its inexhaustible riches, pouring them into the sea, feeling richest, as the sun does, when the poorest fisherman is rowing with golden oars!” Here this state is identified with nature, with the sun, hub of nature, which gives inexhaustibly its energies to all life without asking for anything in return, and in this gratuitous outpouring creates all life and creates beauty. Pouring its gold into the sea such that the poorest fisherman rows with golden oars. That state would be the highest and also most natural state of humanity.

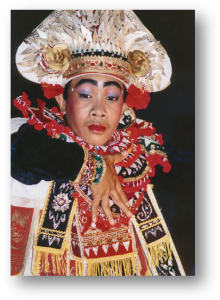

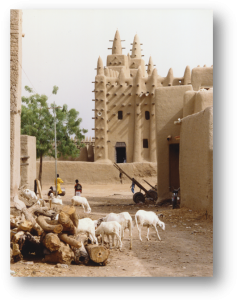

The exultant embrace of the world with superabundant energies is creative. Creative of knowledge, which reveals and opens us, far beyond the limited sphere of human needs and concerns, to the vastness and complexity of the universe, to the songs of the cicadas that emerge only every 17 years, the songs of the sperm whales in the ocean abysses, the solar wind that illuminates the curtains of the aurora borealis, the 67 moons circling the planet Jupiter. Creative of paintings and sculptures that enhance and hold the ephemeral blush of a young woman, the glitter of autumn on a mountain lake. Creative of temples that enshrine mountains and caves and sky. Creative of songs and dance with which we join the songs and dance of nature. “‘O Zarathustra’ the animals said, ‘to those who think as we do, all things themselves are dancing. They join hands and laugh and flee—and come back’” (Z III, The Convalescent, 2).

The exultant embrace of the world with superabundant energies is creative. Creative of knowledge, which reveals and opens us, far beyond the limited sphere of human needs and concerns, to the vastness and complexity of the universe, to the songs of the cicadas that emerge only every 17 years, the songs of the sperm whales in the ocean abysses, the solar wind that illuminates the curtains of the aurora borealis, the 67 moons circling the planet Jupiter. Creative of paintings and sculptures that enhance and hold the ephemeral blush of a young woman, the glitter of autumn on a mountain lake. Creative of temples that enshrine mountains and caves and sky. Creative of songs and dance with which we join the songs and dance of nature. “‘O Zarathustra’ the animals said, ‘to those who think as we do, all things themselves are dancing. They join hands and laugh and flee—and come back’” (Z III, The Convalescent, 2).

The domain of the passions, surging in anxiety and exhilaration, is, Georges Bataille says, laughter, tears, poetry, tragedy and comedy, play, dance, music, ecstasy, the magic of childhood, the funereal horror, eroticism (individual or not, spiritual or sensual, corrupt, cerebral or violent, or delicate), the divine and the diabolical, the sacred, of which sacrifice is the most intense aspect, intoxication, combat, crime, cruelty, disgust. This domain outside of utilitarian existence Bataille calls “the festive” (AS III, 230-1)

In designating the multiplicity of impassioned experiences “the festive,” Bataille indicates that the impassioned self is not isolated, closed in itself. We laugh and we weep with others. Before the collapse of laborious projects or pompous behavior or the disintegration of a sententious discourse into nonsense we laugh, we look at one another and are indubitably aware of what each sees and the pleasure each knows in peals of laughter; we are transparent to one another. In tragic and comic art our extreme emotions surge together; in dance and carnival our anxiety and exhilaration surge like crests of waves spreading among us, in erotic passion each is excited by the excitement of the other, the pleasure and torment of each invades the other.

Juan and Miguel descended Cerro Aconcagua and returned to Buenos Aires. Then what? They had not simply known feelings and emotions on the mountain that they could observe, judge, manage; they had known impassioned states that were undivided between mind and body. Far from family and business that had constructed Miguel’s identity, far from office that had constructed Juan’s therapist identity, there surged forth an impassioned self, an awestruck self, a self asserting itself in terror and rage, a hitherto unknown unsuspected self that in obstinacy and courage pitted itself against exhaustion and pain. They had known the anxiety and the exhilaration of transgressing the boundaries set by nature and society.

These are not experiences that reveal the meaning of life and of the world; they encounter the inhuman, the destructive, the indifference in the substance of reality. They are not experiences that will be integrated in Miguel’s everyday life in Buenos Aires, a life devoted to order and productivity and to the accumulation of commodities beyond all needs and wants. They open, outside of the sphere of reason and work, upon the domain of the festive.

Will Miguel driven violently from Cerro Aconcagua find himself bent on returning? Will he find himself attached to remote and forbidding landscapes, going back to the Andes, going to the Sahara, to the Ice continent of Antarctica?

Will he deepen his passionate attachment in reading books, viewing documentaries, himself speaking, writing, creating? Will he become an environmental activist?

Or perhaps he will remember the climb as a time in which he dared and risked as never before, and in the pain and exhaustion found he had resources to endure he did not know he had. Perhaps he finds in his office other mountains to climb. Perhaps he will rethink his real estate business, learn new computer technology to make it more efficient, train new employees. Perhaps his days, his weekends will be filled with things that have to be done, things that have to be said. Perhaps the urgency of things that have to be done and said will take the place of the meaning he had once sought for.

Three times now Juan has gone to Aconcagua and turned back before reaching the summit. Which of his next patients—banker, middle-aged housewife, college student–is going to hear the advice to climb Aconcagua with him?

References

Georges Bataille, The Accursed Share, vols II & III, trans. Robert Hurley

(NY: Zone Books, 1993. Cited as AS.

Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, trans. Brian

Massumi (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987). Cited as T.P

Philip Fisher, The Vehement Passions (Princeton: Princeton University

Press, 2002). Cited as VP.

Immanuel Kant, Critique of Judgment, trans. Werner S. Pluhar (Indianapolis: Hackett,

1987). Cited as CJ.

Friedrich Nietzsche, The Gay Science, trans. Walter Kaufmann (NY:

Vintage, 1974). Cited as GS.

Thus Spoke Zarathustra, in The Portable Nietzsche, trans. Walter

Kaufmann (NY: Viking, 1968). Cited as Z.

Steven Goldman – The Homeric DSM/ A Corrective Historical Experience

The Homeric DSM / A Corrective Historical Experience

Steven Goldman, Ph.D.

(Click HERE to open this article in the reader.)

Introduction

The question I am exploring with you today is how to become one soul. My theme is the soul and I’m focusing on that small part of existential psychoanalysis that concerns not analysis or existence but psyche or soul. I will trace some of the history of the idea of the soul — and of psychological unity — whose trajectory runs from ancient times to the present. The point I am trying to make today is that when we understand the history that precedes existentialism and makes it possible, we are in a stronger position to take charge of our lives — and thus to do some good.

In my remarks today I am claiming that history is too important. We need it to be less important so that we can be free for creative responsiveness to life. The crux of the issue is that history becomes too important when we become trapped in a single, obsessional vision of the past. Thinking historically helps to liberate us from the tyranny of one idea above all others — this helps us get oriented in our thinking about contributions from thinkers like Binswanger, Jaspers, Heidegger, Medard Boss, Rollo May and Irvin Yalom — some of the founders of the therapies we are exploring in this conference — all of them thinkers who envision a new kind of freedom. Freud, working with Sándor Ferenczi and Franz Alexander, envisioned something like a corrective emotional experience — a way of talking about what is therapeutic in analysis. My addition here is on behalf of the same ambition to free ourselves from the past. But I am arguing for a corrective historical experience, to liberate us from the strictures of a narrow and disempowering conception of history — thus a way of talking about what is therapeutic in studying history. I am reaching for a way of reclaiming the past from blank facticity, to serve the cause of creative self-determination.

I am claiming that what we are able to do in thinking runs parallel with what we are able to do in life — we cannot jump ahead of ourselves into the future, but at the same time we have to fight against the inertia of the past. So I’m discussing existential psychoanalysis, which I define in Yalom’s terms as a dynamic approach to therapy which focuses on concerns that a human being faces just by being alive — and my point of view emerges from thinking about the history of philosophy. Jaspers — an important contributor to existential thinking and a physician credited with inaugurating the “biographical method” in psychiatry — i.e., taking extensive background histories and noting how patients themselves feel about their symptoms — held that psychotherapy is not grounded in medicine but in philosophy, which is why it demands to be examined from an ethical point of view. And I am claiming that when we carry this out, and examine psychotherapy from an ethical point of view, we free ourselves from obsessional thinking — we are forced to confront ourselves and the world we live in — this means that we take responsibility for ourselves — whatever may befall us, despite immensities of limitation — in Yalom’s terms “responsibility acceptance is equivalent to a positive sense of life meaning” — which I would call intelligible freedom or more simply the examined life.

(1) the Homeric Background

The history I am following today begins with the soul or psyche. This Greek term, psyche, the basis of English words like psychology, psychiatry, psychic, psycho, is a feminine noun with the sense “breath, life breath, life spirit,” a kind of wind or air or ether in us without which we begin to swoon, faint, and lose consciousness, but which also underlies powers with more restricted senses, such as heart, appetite, mind, sense, understanding, or even the person himself — as separate from everything about him; also the shade, the ghost, the departed soul, as opposed to any physical or outward thing — very like the Hebrew term nefesh, or vital spirit — what in Latin is called anima. In this conception, the body is merely a kind of envelope which, after death, rots and becomes nothing. But the body-severed soul lives on in some nether state — in Hades, in Sheol, in Limbo, an idea that we see in virtually all primitive cultures and which the Structuralists, for example — thinkers like Saussure, Lévi ?Strauss, Roman Jakobson, Jacques Lacan — referred to as an inevitable premise of human reasoning.

We can see this idea at work in the earliest written documents we possess, for example in the first line of Homer’s Iliad, which speaks of Achilles’ anger and the destruction that follows it for his people the Achaians, “which threw down many strong souls (psycha) of heroes into Hades, and gave their bodies to the delicate feasting of dogs, of birds, so that Zeus’ planning was fulfilled, from the day on which Atreus’ son Agamemnon, king of men, and brilliant Achilles, first fell into conflict.”

It occurred to me that we might create a kind of Homeric DSM — a Homeric diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, for categorizing different sorts of disease conditions of the soul — as a precursor basis for understanding how we look at psychological phenomena today. Homer introduces a number of terms for normal psychological functioning, as well as terms for disease conditions of the soul, just as we do, and many of the terms we use for these ideas today, both in everyday language and in medicine, are descendants from Homeric times. Here is a comparative list:

Homer

Psyche — soul

Eros — impulse

Logos — reason

Mania — madness

Hubris — arrogance

Miasma — pollution

Nemesis — wrath

Pthonos — jealousy

Nous — mind

Kradie — heart

Phrenes — wits

Thumos — spirit

Epithumia — desire

Ecstasis — frenzy

Agon — struggle

Moira — fate

Até — blindness

Soma — body

Akrasia — weakness

Aidos — shame

Ataraxia — calm

Autarcheia — independence

Bouletikon — planning

Prohairesis — choice

Enkrateia — self-control

Etor — heart feeling

Ker — heart thinking

Hexis — habit

Katathesis — assent

Hedone — pleasure

Sophrosune — temperance

Sophia — wisdom

Phantasia — imagination

Timé — honor

DSM – V

Neurodevelopmental /

Neurocognitive disorders

Bipolar disorders / cyclothymia

Depressive disorders

Obsession Compulsion

Substance disorders

Schizophrenia, psychosis

Trauma / stressor disorders

Anxiety disorders

Somatic symptoms disorders

Dissociative disorders

Gender dysphoria

Disruptive disorders /

Impulse control disorders

Personality disorders

It is easy to sort out the Greek roots of most of the current DSM vocabulary — e.g. neural, cognitive, cycle, schizoid, phrenetic, somatic, dysphoria, trauma — but the connection here is not simply linguistic. In many cases the modern terms follow a logic exactly parallel to their ancient counterparts. An example is the term até, which means something like ‘bewilderment, infatuation, or reckless impulse,’ and which was sometimes considered a kind of ‘judicial blindness’ sent by the gods. The idea of judicial blindness — of divine workings behind mental phenomena — foreshadows and offers a useful parallel for the contemporary idea of repression — of psychological material that is repressed, that is rendered ‘unconscious,’ and thus not allowed any outlet, which nonetheless escapes these confines in some unsuspected and often embarrassing way as the ‘return of the repressed.’ Até was personified as the goddess of mischief, ruin, disaster, catastrophe or reckless conduct, yet at the same time até was a psychological condition understood as a kind of sickness — a normal attribution from everyday life in the community, and one that was disparaged. States of the soul, especially overwhelming disease conditions of soul, thus appear as personified forces — as Gods — so that a myth recounting epic deeds of Gods is, at the same time, a story about human beings caught in the grip of powerful forces of nature (a condition examined at length in E.R. Dodds’ classic study from 1951 The Greeks and the Irrational).

Terms like mania (madness), hubris (arrogance), miasma (pollution), nemesis (wrath), pthonos (jealousy), point to a kind of fragmented psychology, in which disassociated part-selves assert themselves against what Homer calls nous — mind — just as powerful Gods assert themselves and overwhelm the plans of mere mortals. Psychological wholeness, on this picture, is still inchoate or as yet barely conceivable — not yet fully realizable, in the same sense that human nature is as yet still unthought in its own terms, but instead is laid out against the high-altitude world of the Olympians — a scene perhaps something like these heights just behind us here in Montana.

Let’s get some of the vocabulary on the table and begin to look at some entries in the Homeric DSM. Of course the term psyche is the most basic of these terms. Homer tells us that the psyche leaves the body at death through the mouth or through a wound or by the loss of blood — later in history, pre-Socratic and Hippocratic writers assert that psyche inheres in the body as blood. Each of us has only one psyche and, once the psyche is departed, no return of the psyche is possible. It appears that the psyche is not the self or the personality and in some ways it seems almost devoid of personality. Sometimes the term is translated as life, sometimes as ghost, for example as we see in the Odyssey, when Odysseus visits the shades of his departed family and comrades as they wander the land of the dead (Book IX). Psyche appears to look and sound just like the person who carries it in life. Yet psyche does not appear to have any specific mental or emotional functions — it is more natural to use another word in talking about human powers. If we want to understand the mental and emotional activity of Homeric man, we have to look at terms such as thumos (spirit), kradie (heart), nous (mind), and phrenes (breast, lungs, diaphragm, heart as the seat of thought — the location of our mind or wits or sense — what in Latin is called precordia) — also words like mania to explain unusual states; also hubris, excess or infatuation, typically punished by até, disaster, for psychic diseases — with mixed elements of human responsibility and divine retribution.

The Greek scholar A.W.H. Adkins sums up many generations of work in classical studies when he writes in his definitive study From the Many to the One: “Today we are accustomed to emphasize the I which takes decisions and also expressions such as will and intention. In Homer there is much less emphasis on anything like the I or its decisions. The functions of the self take the foreground and enjoy a remarkable amount of democratic freedom.” Thus men act as heart or spirit or lust bids them. Odysseus for example wonders whether to attack the Cyclops, but another thumos restrains him. Athena asks Telemachus to offer her a gift — whichever one his kradie chooses. Most famously, anger rises up in Achilles in his argument with Agamemnon, and Homer says that Achilles’ shaggy breast was divided two ways, pondering whether to draw his sword and attack, or else check his spleen and keep down his anger — these weigh evenly in his mind and spirit, but Athena suddenly appears behind him and holds him by the back of his hair, saying that mother Hera had sent her to restrain him — and he says, “Goddess, it is necessary that I obey you two, though my heart is full of anger — because I know that if I obey the gods’ commands, then they will listen to me as well” (i, 218).

(2) philosophers discuss the question

There is a passage in the Iliad (xxiii, 698) that four of the great thinkers from ancient times — Anaxagoras, Democritus, Plato and Aristotle — all discuss. This passage draws their attention because of the way Homer describes the psyche — it is a problem-text and invites different interpretations. The setting is the funeral games that Achilles has decided to put on in honor of his dead friend Patroclus. Among these games is a boxing match between Epeius and Euryalus. Epeius overwhelms his opponent and Euryalus is quickly flattened, carried out of the ring and laid out on the floor allophroneonta, ‘wandering in his wits.’ This unusual term — allophroneonta, ‘confused thinking’ — is also sometimes translated as ‘senseless, witless, distraught in one’s thoughts’; in other contexts it means something like ‘thinking of other things,’ or ‘paying no heed,’ or ‘entranced in his own train of thought.’ Thus the term indicates in some cases psychological dysfunction following the onset of some unusual condition — in this case, a blow to the head — but in other cases it reads as an otherworldly cast of mind — a sense of ecstasy or even an out-of-body experience.

Democritus comments on this passage that mind and soul are the same thing and that we are in brief exactly what we think (Fragment 171). Today we would call this a rationalistic kind of mistake, in which we identify the entirety of human psychology with conscious reasoning, thus ignoring the irrational parts of the soul, things about us that we are not aware of, forgotten or unconscious or forbidden thinking that slips out in mysterious ways (see Aristotle’s review of his predecessors in Metaphysics, Book I).

Anaxagoras comments on this passage in remarking that “mind sets the whole in motion” (Fragment 13) — that is, mind is the cause of the world — mind is the basis of phantasia, mental seeing or imagination, i.e. what we see in the sensorium of consciousness; which implies that the world the opens up to us in sensory experience. Today we would call this an idealistic kind of mistake, as implying that the perceptual world is ultimately a human construction, thus a delusion and species of unreality.

Plato and Aristotle attempt to steer around both these mistakes — rationalism and idealism — and by doing so arrive at contradictory, rival and still influential solutions — both launching forward from Presocratic thinking and especially from Socrates’ two key ideas about psyche or soul: first, that we should know it and, secondly, that we should care for it.

Plato often cites Homer in showing that psyche obviously includes different powers, parts or functions. But his arguments always steer towards reconciling difference and creating a harmony from dissonance. In the image from the Phaedrus, psyche is a charioteer reining in her black and white steeds — earthly desire and heavenly spirit. The inexperienced soul is still green and foolish. Becoming enamored of matter, it seeks to unite with it and become a body itself in order that it might drink in bodily pleasures, but matter is recalcitrant and keeps up its game of enticing and withdrawing. As we strengthen the logos, the phrenes, the nous, our epistemic or knowledge-gathering capacities, the soul is roused from its earthly slumber in the body and reminded of its destiny in a higher intelligible world. It remembers its duty to seek the intelligible through study of philosophy, and to the extent that the soul becomes addicted to this study, it will be able to achieve its release and rejoin the intelligible world. Intellectual insight thus appears in parallel to kind of religious purification; and the therapeutic virtue of philosophy is not merely physiological or psychological, but also religious.

Plato divides psychological conditions into curable and incurable (Gorgias 526, Phaedo 113, Republic X, 615). Psychological treatment for curable mental conditions is a form of education. But for incurable souls — including especially tyrants, princes, and political rulers who practice forms of injustice in civic affairs, and who are models for us of human weakness — a kind of epistemological dysfunction is at work, or inability to learn anything from experience — also a self-satisfaction of arrogance that prefers holding power in an illusory state of mind, to powerlessness in a state of lucid consciousness. When Plato uses words like miasma or nemesis or pthonos (pollution, wrath, envy), he also adds comments with his master Socrates’ irony, so that the personifications of these powers — their transfiguration as Gods — always return us to the problem of taking control of ourselves (“The priests at the temple of Zeus at Dodona used to say that the first prophesies came from oak trees. People in those days, lacking the modern wisdom we have today, were content in their simplicity to listen to trees and rocks, provided that they spoke the truth,” Plato, Phaedrus 275b).

Plato’s philosophy proposes that human beings have some power over their actions — likewise he argues that this control is mainly a function of intellectual intuition — that is, on the agent’s glimpsing of the Forms, which again is Plato’s image for an intellectual achievement — and however limited this idea may be, it encapsulates one of the founding insights of existential psychoanalysis — the idea that thought and emotion are bound up together; yet phastasia (imagination) is distinct from katathesis (assent); i.e., what we feel is bound up with judgments we are making, and if we are laboring under some error and making a poor judgment, then in the case that this judgment is exposed and we actually change our mind, then with the change in the content of our judgment, the emotion encrusted around it, and emerging from it, also changes. This important idea informs Stoicism, Theraveda Buddhism and, much more recently, what is now referred to as Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT).

Aristotle’s view of the soul is more complex. A human soul is first of all an animal soul. But the phusis (nature) of the human soul is such that by phusis man is a creature who lives in a polis — man is a political animal — human flourishing exists in and depends on society (Politics, Book 1, 1253a). And I think in a way Aristotle has overcome some of the limitations of a Platonic view of the self, just as Heidegger overcame some of the limitations of the Cartesian view of the self — not the lonely self that glimpses the ideal Forms, not thought as opposed to extension or the agent in us that knows, the “thing that thinks” — but what Heidegger calls being-in-the-world, and what Buber calls the I-Thou experience, or existence as encounter — a sense of ourselves that we get from a social context, that takes form and evolves in interactive relationships. Human being is not accidently a social kind of creature, but everything we are as people who feel, think and act emerges in the rich context of family, school mates, friends, colleagues, lovers, co-workers, and fellow citizens — outward from the primordial society in the family, towards the limit of what the Stoics called “cosmopolitan” — thus a way of belonging to, and taking care of, the world.

If we look at all this work together, we see a portrait of the Greek personality that has not yet developed a firm and stable structure which we would regard as normal. Scholars such as E.R. Dodds, A.W.H. Atkins and Werner Jaeger argue that the failure to develop an egocentric personality in Greece is closely linked with the structure and values of Greek society, which necessarily externalize criteria of action and give no importance at all to intentions, to mere thoughts, rather than the consequences of human actions. This suggests that the achievements of the Athenians in particular — although outstanding — were bought at a very high price. Thus paradoxically it is only with the loss of the polis — the body of citizens — one’s city, country or community — in Latin, civitas — regarded by our Greek ancestors as being the only place in which a good life, or genuine happiness, was possible — it is only when the city is lost that any solution appears to pry society loose from the strictures of a results-culture. That is: the only way people could develop an inner life, a sufficient inwardness to develop something like a moral conscience, was by destroying the warrior-culture competition that gave birth to the polis in the first place.

An important stage in this history is the development in Stoicism and Epicurean philosophy of ideas such as apatheia — indifference or dispassion — and ataraxia –contemplative, lucid tranquility. Thus as the Greek city-state crumbles and is replaced by the Empire — Alexander’s empire and Rome’s Empire and Christianity’s empire — the focus moves from the role one plays in a tribe — a small society — to a new focus on the development of the self in the context of an enormous megalopolis, over which very few people — if even any — have the slightest chance of altering its headlong pace of change. The focus is on oneself — as Epictetus says, “on the things which are in our power” (Discourses 1, 1). The trajectory here is enormously complex. In one sense the movement is from godlike pride to humble strength — from transcendental narcissism to a reality-based ego — from aspiration that swamps all human feeling to an accepting humility more inclined to understand than conquer. In terms of psychological unity, there is movement from psychic chaos to genuine selfhood — from a concrete mindset to psychological insight — from dissociation to integration — from many to one — from the fragmentation of spirit and heart and impulse at war with each other, to one person feeling and thinking different things and trying to sort them out. All these developments run parallel as the deep foundations for a stable kind of personality and an end to the storm and tumult of the Homeric conflict-psyche.

(3) a summing up

Classical scholars observed centuries ago that the ancient Greeks did not possess a concept of the will. Recent writers such as Max Weber, Karl Jaspers and Hannah Arendt argued that the encounter between Greek shame-culture and Judaic guilt-culture brings about the epochal change in the Western psyche that makes it possible for people to think of themselves as having a power of will, as making choices and being the authors of their own lives. Scholars such as Pierre Hadot, Albrecht Dihle and Michael Frede document what Stoicism contributes here — the huge step forward in the ideal of Stoic self-command. Especially in Christianity, and with its intense inwardness and focus on prohairesis, or explicit choice, thus assertively (and even counterfactually) taking a side — we get to a place that (paradoxically) is less the real-world, less the world of facts and positions in society, and is more the dream-world, a world of wishes and hopes for social change. On the wings of imagination like this, we give ourselves a bit of breathing room and space for self-development, to create the interior world of thoughts — the life of the Mind — the complex subjectivity that grants a person what Kierkegaard tells us is an infinite freedom (Concluding Unscientific Postscript, 1846) — the kind of freedom that Camus and Sartre and Unamuno articulated — a tragic freedom, a condemnation to freedom, a dizzying, confusing freedom, what Nietzsche called the heaviest of all weights (The Gay Science, 1882) — an ‘existential freedom’ in which the whole person awakens and begins to make authentic choices — a world where we make ordinary and also outstandingly bad mistakes; a world of ordinary good things and also things that are remarkably good; — that is: choosing to see the world in all its vast complexity, and as it really is.

This is the third insight emerging out of a long stretch of cultural history informing existential psychoanalysis, from three precursor forms in the ancient world: —

1 — the distinction between imagination and assent (phantasia kai katathesis)

2 — the redefinition of man as a political animal (politikon ho anthropos zoon)

3 — the psychology of acceptance in struggle with suffering (ataraxia kai apatheia)

I am arguing that these ancient ideas about the mind, politics and the role accepting plays in developing mindfulness, precede and make possible existential psychoanalysis.

By this teaching, the only person in this world I can control is myself — yet –strangely — I cannot control even my own flow of thoughts — but only where I give my assent. By this teaching I cannot be a self on my own — I get to be an ‘I’ in an enormous context and with an entire world of people — thus I exist in space and also in a web of relationships — I am a physical entity, but I am also inherently political in my nature. And because I am inherently political in my nature — because I am in dispute — I am free — which means: I can practice assent; I can practice politics; I can be whatever I have the strength to see and do — or instead remain a slave, because the political world in which I live is corrupt — or because I am. I am returning to the existential claim that freedom consists minimally in my attitude towards whatever happens to me — in Rollo May’s formula, freedom has to do with transcending the immediate situation — the self is simply “the ability to see oneself in all one’s self-world relationships and possibilities” — not to be rigidly confined to a specific world, or any specific obsession — which Binswanger calls “fighting against the confines of a single world design” — to which he adds what he considers the main point, that we have to see ourselves as in-the-world the way we really are before we can take any step beyond-the-world, and become at home in what he calls the eternity (Ewigkeit) and haven (Heimat) of love. This existence we are living, he says, can be at home, or not, in this place, entirely by the force of our choices — i.e. by the power of will.

The ideas of will and of choosing freedom emerge from the long history that begins with the Homeric DSM and ends with ours — terminating in a concept of transcendence. This is a point of view which takes the world as a point of departure for a flight on which everything depends — which each person must venture on his own, by his own choice, and which can never become the object of any doctrine. Jaspers makes the interesting comment that while medicine pathologizes and tends to undermine individual self-determination, philosophy instructs and tends to support self-definition — yet we have to rely on both. This means that there is an irresolvable tension in human being — we are psyche and soma at once — the psyche is many things, and so is the soma — which means that we can never wholly unify our souls, or ever become one thing.

Thus my inquiry is a failure and I have no formula for achieving psychological unity. And this failure I think is exactly the point of this subject whose history I have been tracing, and for my conclusion I will try to say briefly why I think this is so.

We may feel sometimes that we are too many people at the same time and that there is just too much chaos and confusion inside of us. In other cases the problem is that we are stuck being exactly the same narrow person over and over again. But if we think through both these problems from the standpoint of the history of philosophy — if we trace the history from Homeric times and think through what thinkers like Nietzsche and Yalom have argued — we see that we have to reject the whole issue of unifying the soul and replace it with something else. The real issue isn’t about being one person throughout life, or getting to the point where you don’t feel drawn in different directions. The issue is how to live a good life. Thus I think we have to get away from the teaching about unifying our soul, and stick with the question about the good life.

Pythagoras coined the term ‘philosophy’ and offered the analogy between intellectual curiosity and romantic pursuit. He argues that we cannot know what the good life is but can only seek it. That is: the good for man is to search for the good for man. The focus of our lives is on ethics — but we are pursuing ethics as an inquiry rather than a doctrine. The gain of thinking about philosophy as a form of love is that this makes the case for the uncertainty of philosophic reasoning and offers the perspective that philosophic vision is subject to change. Psychopathology is in brief a refusal to change. The good life — psychological health — is something like the ability to change; it has more to do with accepting. Our Greek ancestors and especially Stoicism define this idea and I think in more recent times Wittgenstein had something like this in mind when he writes that “the solution to the problem of life is seen in the vanishing of the problem” (Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus 6.521) — not that the problem is a pseudo-problem, that it is a false problem, or an unimportant problem or even nonsense — but that eventually you find a way of handling it — eventually you find your self-confidence, your gameness, and you simply immerse yourself in the river of life.

Afterthoughts and objections

I am tracing some of the history that precedes the development of the modern personality. In the same sense in which the therapeutic relation can be viewed as a kind of emotional realignment and “reparenting” process — a way of restarting the human project with fewer deficits and more freedom of action — I am envisioning a kind of historical realignment and “rehistorizing” process — another attempt at overcoming entrapment in a narrow conception of what is possible in human reality. This is the general sequence of argument that emerges from the re-history project:

1. Vocabularies of explanation (Homer and DSM each in various versions) change.

2. We cannot solve our problems, once and for all, without having any more work to do; there is no final vocabulary of explanation; just the latest. Mythologies of passivity come and go, and we may sacrifice our freedom of assent, of political engagement, and struggle in the face of suffering, to any of them, to our detriment.

3. The ancient teaching about unifying the soul is correct, but it is in effect the teaching that asks us to unify Being — e.g. to unify the two worlds, above and below, sacred and profane; and of course this is exactly what we should do. This is a kind of project that we are working on or should be working on. But it is strange to think that we can set out to do this kind of work without having settled on a final meaning and brought the work of unifying our soul to a completion. Despite this we gain experience and reach steadier states of competent/happy being than earlier, less steady states — we get older, we evolve a little bit — we are a little wiser and a little more unified than before — perhaps; in some cases but not in all. It is strange and in a way counterintuitive to think that we can do good work on any project with a divided soul. Work that emerges from a divided soul is a patchwork and does not let the soul shine in what it can do. Of course we want to act as a whole being and be all of a piece instead of remaining a motley jumble of instincts, memories and plans. It seems clear that we can’t unify ourselves in the middle of the work we are doing — we have to do this beforehand, before the work gets going, so that our best work will shine through; so that we work out of a place of wholeness and let the things we have to offer come forth. But in effect there is no beforehand. You cannot reach or get back behind yourself. There is only the now — there is the thing to do now — there is always new work to be done — the soul always has contradiction in it — so that against our own principles, and against the dream of unifying the soul, we eventually have to give up the dream of unifying the two worlds and work more simply, just to do some good.

4. For which we have the question, what is the good, anyway? and thus the ongoing practice of philosophy, i.e., to ask this question and go on with it through life.

I should say that in conceiving this work and in developing the argument that comes to the conclusion that I have expressed as a corrective historical experience, I have been guided by my study of the works of many classical scholars and historians, including many who reach nearly opposite conclusions, which in outline I want to review here.

Bruno Snell, The Discovery of the Mind: the Greek Origins of European Thought (Die Entdeckung des Geistes, 1946) — a hugely important source for thinking about ancient man’s psychological understandings — begins with Greek ideas about the body. Snell argues that, exactly like their ideas about the psyche, the Archaic Greeks also appear to have conceived the body in a fragmented way, as a collection of unlike parts. In their vocabulary, at its most ancient layer, there is no provision for the body at all. Snell demonstrates that the term soma comes late in Archaic times; before this there are words such as guia, melea, both meaning limbs, demas meaning the frame, chros the limit of the body. Snell claims that the early Greeks simply did not grasp the body as a unit — this is one of his most startling and counterintuitive conclusions.

Psyche — the subject of Ervin Rohde’s pioneering study from 1903 (Psyche: Seelencult und Unsterblichkeitsglaube der Griechen — Psyche: The Cult of Souls and Belief in Immortality among the Ancient Greeks) — is the force that keeps the human being alive during its life. Conceived as the life principle, the idea of psyche also stirs up questions about the possibility of life after death. Rohde (a friend of Friedrich Nietzsche) and Snell both investigated the somewhat mysterious function psyche plays during life. Both conceived the point of studying history as enlivening our insight, and empowering our actions, in the now.

Snell mentions that Homer does not appear to know the idea of depth as applied to internal states. So there is nothing like deep knowledge, deep thinking, deep feeling. Priam laments the fate of Hector by saying that “I groan and brood over countless griefs” (Iliad 24.639); quantity, not intensity, is Homer’s measure of importance. This goes to the idea that ancient man did not conceive psyche as a place where everything transpiring in consciousness is collected together, which might be sounded down to its primal beginnings.

Snell says that Homer, in his descriptions of ideas or emotions, never goes beyond a purely spatial or quantitative definition; he never attempts to sound their special non-physical nature. Ideas are conveyed through the nous, a mental organ analogous to the eye (Iliad 14.61). Consequently to know is eidenai, which is related to idein, to see, so that ‘to know’ means something like ‘to have seen.’ The eye serves as Homer’s model for the absorption of experiences (as Socrates thinks of knowledge in terms of handling physical material; as Plato thinks of knowledge in terms of mental seeing, or the intuition of essences — a concept Husserl develops further in his 1913 work Ideas; these become important steps for Heidegger in his discovery of being-in-the-world). Thus the intensive coincides with the extensive — he who has seen much is he who has amassed much knowledge — wide-ranging experience engenders true knowledge.

There are no divided feelings in Homer. We have to wait until Sappho to read about bittersweet Eros (the classic source on this remains Wolfgang Schadewaldt, Sappho, Dasein in der Liebe, 1950). Homer is unable to say: half willing, half unwilling. What he says instead is: he was willing, but his thumos was not. This means that there is no contradiction within one and the same organ — within one and the same I — but instead there is contention between a man and one of his organs — his powers or functions or senses. It’s like saying: my hand desired to reach out towards (x), but I withdrew it. That is: two different things or substances are engaged in a quarrel with one another. Snell draws the conclusion that in Homer there is no genuine reflection — no real dialogue of the soul with itself — which implies that genuine reflection depends on a kind of normalized dissociation — a contradiction within one and the same I.

We can see a kind of change from this condition in Heraclitus (fragment 115) where he says that psyche has a logos which increases itself. Thus apparently the soul has something capable of extending and adding to itself of its own accord. So the soul is a kind of base from which certain developments are possible. But we do not attach any similar ideas to the eye or to the hand. For Homer, mental processes have no such capacity for expansion; we can become experienced, but mind does not do this itself.

Thus the augmentation of bodily or spiritual powers is always effected from without — above all by the gods — not by an inner nature of the human mind unfolding itself.

Snell says that in Homer there are no genuine personal decisions. Even where the hero is shown pondering alternative courses of action, at the end the decision is made after the gods have arrived and tipped the scales in one direction or another. Thus there is always a divine meddling and that above all leads to resolution and action. Another way Homer describes these changes is to say that the thumos overwhelmed the kradie; or that one function trumps another.

Snell says that Homeric man has not yet awakened to the fact that he possesses his own psyche, in which he may find the source of his powers, but instead Homeric man senses that he receives his powers as a natural and fitting gift from the gods. Independent psychic powers such as mind or heart have thus a magical connection and existence against a divine background. Despite this, the heroes of the Iliad do not feel that they are the playthings of chaos. That is, they acknowledge the Olympians, and they see the divine world as orderly; the gods have created a well-ordered and meaningful world, even if (despite our trying) we do not understand it.

Snell’s point is that the more the Greeks began to understand themselves, rather than attributing their characters to mythic origins, the more they adopted of the orderly, meaningful Olympian world into themselves. They infused heaven down into earth.

Simone Weil’s The Iliad: The Poem of Force, from 1945, quarrels with the idea that Snell expresses in his claim that Homeric man sees himself living in an orderly world. Weil argues that the true hero at the center of the Iliad is neither god nor man, but force. Gods wield force and man employs force. Force enslaves man and force takes men’s lives. The human spirit is twisted by its relations with force; it is swept away, blinded, deformed, degraded, whether it submits or struggles against it. Force may turn a man subjected to it into a thing; exercised to its limit, it turns the man who wields it into a thing; in the end, in the most literal sense, force turns him into a corpse. Someone was here and in the next minute there is no one here; this is the spectacle that the Iliad drives home again and again; this is the inexplicable final terror of death.

The cold brutality of the deeds of war is left undisguised — plainly rendered to make us stare down the mystery of death. Neither victors nor vanquished are slandered, scorned or hated. Fate and the gods decide the changing lot of battle. Within the limits fixed by fate, the gods determine, with sovereign authority, victory and defeat. The gods provoke fits of madness and create obstacles to peace. War, chaos, trouble, ruin, force — when we finally see clearly, this is what gods want — this is their business. Their motives are thoughtless — caprice and malice — they have no logos. Men are beasts or things neither admired nor condemned, and Weil argues that there is a sense of regret hanging over the scene that men are capable of such degradations.

Bernard Williams’ Shame and Necessity from 1989 quarrels against another of Snell’s conclusions — he argues pretty much against the grain of most classical scholarship from the past century — rather than accept the idea that Homeric psychology shows a fragmented character, he argues that ancient man was much the same as modern man.

Williams denies that Homeric man dissolves into parts, mental and physical. Williams mentions the use of the verb mermerizen, to be anxious or thoughtful. His example is Iliad 24.41 where Diomedes is described as “wondering two ways.” Williams thinks that in some cases, the state of uncertainty for the hero who is wavering between different courses of action closes simply by one course of action coming to seem to the agent, after some kind of deliberative process, to be better than the other.

Williams describes case in which Athena seizes Achilles by the hair when he is wondering whether to kill Agamemnon. She speaks to him and tells him that Hera has sent her and asks for his obedience, and eventually he yields. Williams describes this interchange as a kind of stand-in for seeing that one course of action is better than the other, in terms the agent was already considering; ‘divinity’ gives him an extra and decisive reason, which he did not see before, for preferring one course of action rather than another. Williams argues that the gods are substitutes for a kind of deliberative process that human beings have already begun on their own. Another example is Iliad 10.503 where Diomedes is considering in the heat of battle what would be the worst possible thing to do, when Athena comes and persuades him not to do any of these things, but instead to head back to the ships. Williams wants to describe this as the agent acting on his own reasons, disguised as this divine intervention.